Mission

A leader in progressive education since 1921, LREI teaches children to be independent thinkers who work together to solve complex problems. Students graduate from our diverse community as active participants in our democratic society, with the creativity, integrity, and courage to bring meaningful change to the world.

Approved by the Board of Trustees, October 6, 2014

Progressive Principles

Progressive Pedagogy: the theory and practice of teaching at LREI

An emerging intelligence is the product of the meaningful relationship between knowledge and experience. Dewey defines the work of intelligence as “the formation of purposes and the organization of means to execute them.” Plainly, intelligence exceeds knowledge of content acquired from external sources; it is the synthesis of knowledge and experience, and allows the learner to use what is known, to plan for what is not yet known.

This intelligence flickers at the very youngest age at LREI, when a 4-year-old makes an adjustment to their block structure, having observed the crash of blocks because of a lack of a sturdy base. And in Middle School more explicitly, when an eighth grader meaningfully connects their previous understanding of immigration to current U.S. policies on the southern border. And then, as an eleventh grader uses their skills of question-posing to guide them through sourcing and writing code that helps make sense of data from New York City water plants, and then propose potential implications and environmental impacts.

This is the purpose of progressive education, and the work we do at LREI every day.

Our practice is guided by a set of principles. These principles/beliefs are distilled from both the Theory of Experience, articulated by Dewey, and from the iterative practice of progressive educators at LREI for over 100 years. Though there are additional principles and practices that are enacted in our classrooms, the following list is essential in the work of progressive pedagogy. Our work is to enact these principles in our classrooms each day.

Rising from the epistemological belief that children both come with knowledge, and are capable of constructing knowledge within experience, the ways of knowing that exist in our LREI classrooms are inherently rich and complex, reflecting the experiences of each child. Teachers work to provide learning experiences that continue to carry out this principle, by selecting texts and resources that provide both convergent and divergent perspectives, at age appropriate levels. A central practice in carrying out this progressive principle is in the asking of questions. Teachers deepen the inquiry, and subsequently the understanding, of students by raising questions that push students, challenge their current thinking, and build complexity. Other practices that accomplish this principle are circle meetings/discussions, where each student has space and voice to share their thinking, and writing that asks the authors to use primary sources, literary texts, etc. to make a claim, or produce authentic analysis.

The belief that education is of, by, and for experience grounds this principle. The belief that knowledge is co-constructed within an educative experience, designed by the teacher, is central to progressive pedagogy. Rather than transmitting information to students, teachers set the conditions for learning to take place, relying on the knowledge from the theory of experience, sociocultural theory, and others to guide these decisions. Examples of this principle in practice could include something as simple as a discussion that occurs after reading a text, and students working together to construct their understanding, and synthesize this within their existing knowledge base. An inquiry or investigation of a phenomena is also a practice that accomplishes this principle–with the questions that students pose guiding the study. This principle should be in practice everyday, across the LREI program.

Core to progressive pedagogy of the concept that learning is social, and thus, progressive classrooms are alive with dialogue, with making, with doing. Examples of how this principle is accomplished are endless, but following are a few exemplars that are central at LREI.

Fieldwork: From the Fours through 12th grade, LREI students travel beyond the walls of the classroom to engage authentically and meaningfully with the social world. Field work is the fullest embodiment of educative experience, as students take up positions as researchers in the world. They pose questions, collect data, and return to wrestle with and make sense of all they uncovered.

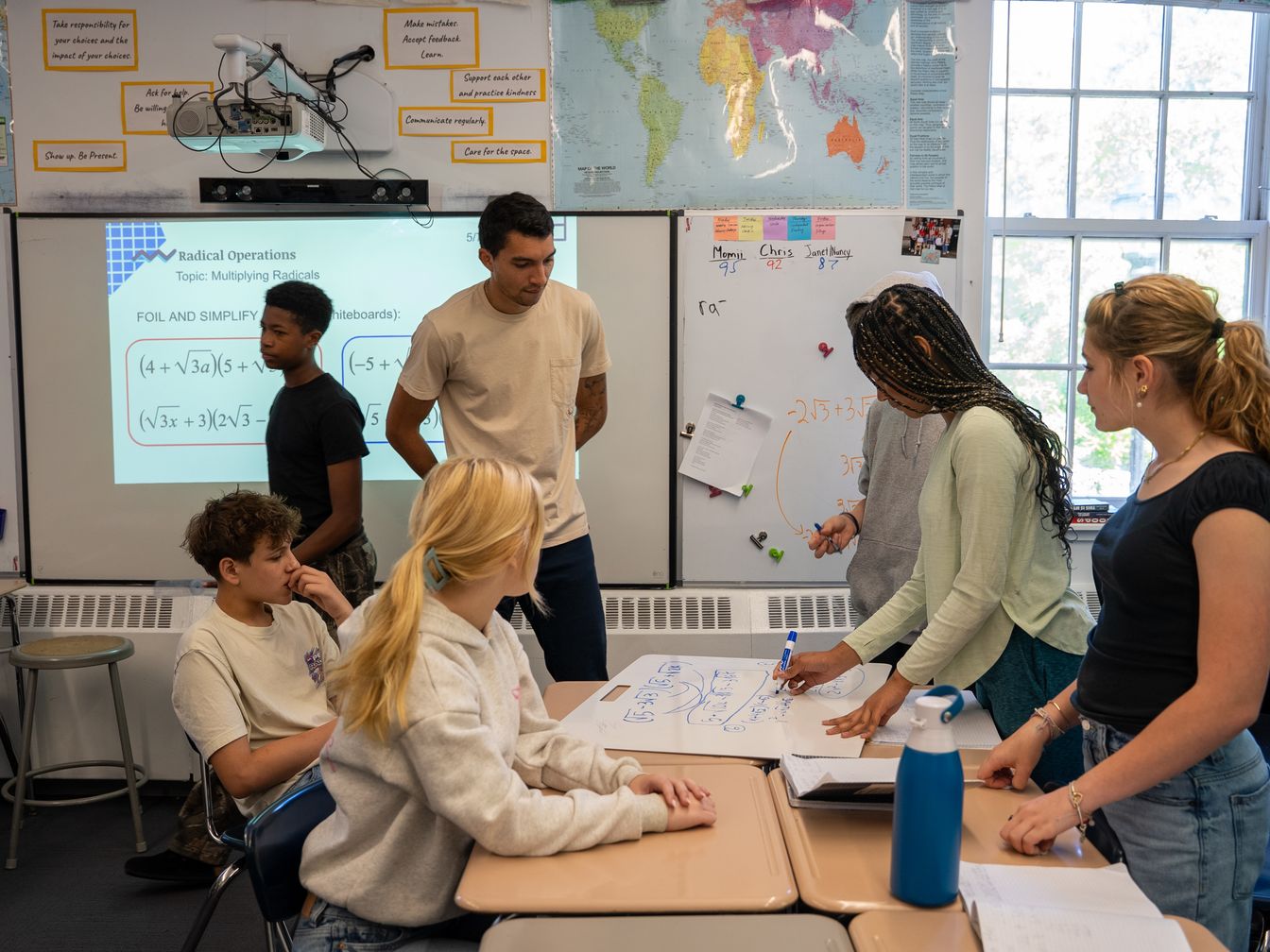

Open-ended materials: In general, working with open-ended materials is a way of reflecting on/processing/making sense of what is being studied; it is about constructing understanding, solving problems, and representing internal knowledge/thought. School supplies and classroom materials are provided as tools with which students can engage in their meaning making work. Though ubiquitous across school settings, classroom tools such as whiteboards, post-it notes, and chart paper are used differently; rather than a space for a replication or re-presentation of facts or knowledge transmitted by the teacher, LREI students use these tools to construct and deepen understanding together, and to grapple with and make sense of phenomena under study.

Block building. One of the most significant, and historic, practices that accomplishes this is the use of blocks as an open-ended material within classrooms. Within the block area, and with support from teachers, children negotiate meaning, test hypotheses, and make sense of phenomena they encounter–whether from the natural world or social one. Beyond the early childhood classrooms, the cognitive work that began with block building extends into the making of prototypes and models that continue to allow students to test their hypothesis and engage in experiments. This principle is accomplished in the upper grades through robotics, science experiments, and 2D and 3D art, to name a few examples.

In progressive practice, learning begins with a question. At times, this question is set forth by the teacher, and at times by students. Throughout a study, iterative questions are raised that move learners toward construction of knowledge, and deep understanding. This particular principle relies on the quality of the question, and is informed by the expertise and knowledge of the teacher and the curiosity and engagement of students. Setting the conditions for rich inquiry is the ongoing work of teaching, as the conditions change in relation to the learners in the classroom.

Knowledge of students by understanding developmental stages, by observation of their engagement and work within the classroom, and by understanding how identities shape learners and their ways of being in different ways is central in the work of progressive practice. The phrase “the whole child” is shorthand for this work. Much of the understanding that teachers must develop occurs before they enter the classroom, through the reading of research and texts that explicate development and identity in relation to the age of the students they teach. And within the classroom, examples of practices that accomplish this principle are choices of materials and curricula that meet students at their zone of proximal development; the physical arrangement of a classroom that communicates understanding of the unique needs of the students in the room, and the physical arrangement of the room in relation to ensuring that each student feels they have a seat at the table; that they truly belong.

Meaningful work is a term used since Elisabeth Irwin and others founded progressive schools, and was central to their daily practice. Initially a response to traditional school and its requirement of learning from textbooks while sitting in desks, this principle has become more important, and more fully realized through the articulation of sociocultural theory. Meaningful work occurs when a learner is authentically engaged in an experience they the can access, and that also pushes them beyond their existing understanding or skills. Sensemaking is an aspect of meaningful work, where students attempt to synthesize a new idea/phenomena into their existing knowledge base, leading to an expanded understanding. Ultimately, meaningful work and sensemaking ensure that learners are making connections within and across their learning experiences, ever deepening their intellectual capabilities. Examples of meaningful work occur within the context of the study of the social world, and within problem-solving experiences across the program. Planning and designing for sharing with an audience, prepping for interviews with people during field work, and organizing for a cause/advocating for change all accomplish this principle.

It has oft been said that the reason that schools do not employ a progressive pedagogical approach is that it is not challenging. When students learn through educative experiences, they develop the critical abilities of observing/considering what is transpiring, making a plan for how to interrogate the idea/phenomena further, apply judgment and critical thinking through iterative cycles of experimentation, and finally, to produce analysis or a plan of action regarding the study. In this iterative learning process, students increase their individual intellectual capacity, so that when they move beyond LREI, they can independently engage in cycles of inquiry as an embodied intellectual practice for life.

Growth that is expansive and ongoing is a signal that students are moving through a continuum of experience leading to a future where they can employ their cognitive capacities independently, in service of an inquiry or study they are engaging in. A continuity of experience is essential, in order to ensure that students are transferring and synthesizing skills and knowledge with increasing agility and complexity. An important practice at LREI that helps teachers tend to this principle is by creating meaningful feedback cycles with students, and through the ongoing sharing of information regarding student learning with families and future teachers. Another example is curriculum that is thoughtfully sequenced, both in relation to development, and also in relation to a continuum of learning experiences that build student agency and independence.

John Dewey articulated this purpose of this principle most clearly when he stated “The epistemological implications of this view [progressive pedagogy] are nothing short of revolutionary. It implies that the regulative ideal for inquiry is to generate a new relation between a human being and her environment--her life, community, world--one that makes possible a new way of dealing with them, and thus eventually creates a new kind of experienced object, not more real than those which preceded but more significant, and less overwhelming and oppressive.” It is the work of education to help move communities toward an ever more just existence, and this educative experience is carried out at LREI most often through the study of the social world, and the interrogation of the complications and complexities that occur in relation to power. Students build their skills in this area from the earliest ages, when they learn to resolve conflicts together by considering the needs of each person, and they expand on this work by considering their own identities and the ways they are situated within systems of power, and finally by listening and learning from stakeholders within other communities who are engaged in seeking justice for the people and places where they live.

Each day, teachers arrive to their classrooms with the responsibility of carrying out this principle in all of the ways they engage with students and design educative experiences. Elisabeth Irwin stated, “At a time like this when everyone is thinking in terms of world problems, it is sometimes hard to keep our minds on the small problems of the day-to-day life of our children. Yet the way that the foundations of democracy are built is by daily habits of recognizing the right of those who differ from ourselves.” Across the LREI 14-year experience, children develop the necessary ingredients of citizenship in democratic societies through their daily work together. They build agency, voice, problem-solving skills, creativity, the ability to think critically about an idea or problem etc. through the negotiations they engage in within the microcosms of their classrooms. Fundamentally, all teachers are working toward the fundamental democratic principle that all humanity matters, and all people should have agency in ensuring that their community is evermore decent and just. Dewey states that, ultimately, the work of progressive pedagogy is the work of democracy, and at LREI we must continue to imagine ways in which we can ensure deeper, more durable ways for our students to come to know this, and believe in their responsibility to it.